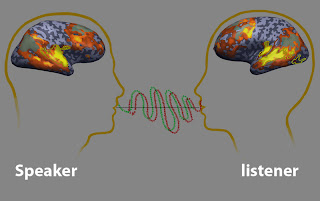

The brain bonding reflected by the matching lit-up neural areas shown in the above graphic is exactly what emotional connection looks like on an MRI, according to the magazine Science, in its article "Mind Meld Enables Good Conversation," July 26, 2010. http://news.sciencemag.org/sciencenow/2010/07/mind-meld-enables-good-conversat.html?ref=hp

Brains synchronize. This is due, say researchers, to "mirror neurons" in the brain that cause partners in satisfying conversation to begin imitating and even anticipating each other's grammatical structures, flow of speech, and even bodily postures. Unconsciously, they've found common ground. In essence, two separate brains form a larger one.

You may be familiar with the term "Mastermind" if you've read Napoleon Hill's Think and Grow Rich. The power of Mastermind groups has been experienced and documented for decades. The result: larger and more effective ideas, insights, and solutions. The emergence of a new way that no one has thought of before.

It's no accident that the trials on which the Science magazine findings are based involved telling stories. Human beings are hard-wired to receive stories at the core level. As cultural historian Daniel Pink wrote in his book A Whole New Mind: "The sorts of abilities that now matter most are fundamentally human attributes. After all, back on the savannah, our caveperson ancestors weren't plugging numbers into spreadsheets or debugging code. They were telling stories, demonstrating empathy, and designing innovations."

Stories bypass the judgmental, intellectualizing prefrontal lobes of the brain, the source of our conscious decision-making, and tap directly into the older and more primitive limbic areas of the brain, where unconscious visceral choice and attachment originate.

In psychology and music, this coupling is called resonance. As a story unfolds, the listener identifies with the protagonist and vicariously experiences through their imagination the emotional states aroused by the situations, choices, and actions of the characters. They internalize the unspoken message of the story, and make decisions from this unconscious place that can override every other practical consideration.

~~~

In my 18 years of facilitating story workshops among every possible population, including groups that were in extreme conflict, I've seen the transformational results that happen when two or more minds are in sync. And I have come to be able to identify the exact moment when it happens: there's a palpable shift and softening in energy, a deepening quiet, a profound stillness. As an example, in the turbulent weeks before the 2004 presidential election, I facilitated a workshop at a conference for trauma therapists who had come to Washington, DC from all over the country. They were ordinary people who reflected the cultures, biases, and experience of their regions.

I could feel the tension as one by one the nine participants introduced themselves, and the distaste as faith-based counselor from the southwest met gay psychotherapist from New York. The young New Yorker had come early to sit quietly by the sunny window and gaze at the Washington Monument across the street. He told me he was overwhelmed with the two traumas affecting his clients: AIDS and 9/11. There were others, but these two defined for me the challenge I faced in facilitating a story experience that would demonstrate to these clinicians the healing power of my non-clinical story approach.

I began with an overview of archetypal stories -- the kinds of stories we call fairy tale and myth -- which have a common structure of crisis, struggle, and transformation, and are thus very effective in supporting recovery from traumatic events. The lack of engagement on my listeners' parts was obvious in their glances at their watches and rifling through the handout.

I began, "Once upon a time..." and launched into a brief version of the end of the Odyssey. This is the turning point, when Odysseus finally opens the way home to Ithaca through telling the stories of his long wanderings after the Trojan War. This myth is powerful not only for soldiers returning from war but for anyone trying to "come home" after tragedy. People began to listen.

(I start my workshops with an old story for two reasons: 1) to take people out of their problematic reality where it's easy to discount or judge someone else's story; and 2) to tap into right brain consciousness, which is the gateway to deeper regions of the mind.)

At the end, I asked my usual question: "What stands out most for you about this story?" There were a few minutes of awkward "brain-storming" -- mostly questions about how this related to helping kids who had been sexually abused, and how to separate one trauma from another in a person's life. The elephant in this room was the toxic distrust that permeated everything in Washington in those days.

Until a woman said that what resonated most for her was Odysseus' 10 years adrift at sea. She had lost her own daughter to leukemia nine years before, and although she was a woman of faith who had gone to many grief workshops and healing retreats, and even though she helped many others deal with their sorrows, she herself was frozen in the "day after."

A shift happened: the group became very quiet and attentive. In the stillness, the man from New York said, "I know exactly what you mean." He described the devastation that surrounded his life as a therapist, gay man, and New Yorker dealing with the double traumas of HIV/AIDS and 9/11. Others chimed in, sharing their own feelings of exhaustion from caregivers' occupational hazard: vicarious trauma.

I invited them to write for 10 minutes whatever came up, without censoring or judging it. And then, if they cared to, to read what they had written to the group.

The woman read about the moment of her daughter's death. As she did so, she raised her eyebrows when she read: "A peace came over Lila's face, and I knew at that moment she was gone, and that she was in the arms of a love greater than even I her mother could give her."

She wept. "I forgot that moment," she said. "I think I can move forward now." Turning to the young man, she said, "Thank you," and asked if she could give him a hug.

As I began to bring the group out of this deep place to a less vulnerable state, we each shared -- myself included -- how much more relaxed we were, less stressed, and feeling that we had truly connected with other people at a level we rarely got to experience, even in our families. Something had happened. Except for the very beginning of the group, we had never discussed the techniques of trauma story; we had experienced all of it in a healing moment. The woman continued to work with me for several years after that.

This is an extreme example, but I hope it shows you how story reaches beneath the thinking, judging mind to the feeling one, from one inner life to another inner life, where we are all human beings together standing on the common ground called life.

Why can't we establish story sanctuaries like this everywhere, where people of all classes and persuasions can leave their ordinary identities, opinions, and lives for a moment and just share their stories? What new solutions might emerge for our disconnected nation and world?

How to Develop a Connector Story

1. Decide what kind of story you want to tell. Ask yourself, what is your audience's most immediate need? What do they want to hear from you? A motivational story, a how-to, a team-builder, or one that ignites creativity. Know what you bring to this encounter.

2. Tell a story that has the elements of archetypal story: crisis, struggle, and transformation. This is the story that all cultures across all times and places tell: A problem or darkness takes hold, someone goes in search of knowledge or an object that can restore light. After an arduous quest, they find it, bring it home to their people. Life flows again.

3. Start with a problem, need, or crisis. Story always begins with crisis and is about how it was either successfully resolved or how it spiraled into tragedy. What was the setting and situation, who were the characters involved, what were the conflicts? What did you want to make happen and what were the obstacles?

4. Describe the struggle. Here's where you can give a bit of history to orient your audience to the difficulty. This can be a back story -- that is, go back before the beginning to describe a long unsuccessful struggle to change or fix the problem. In archetypal stories, heroes generally fail three or more times, learning something new with each defeat. On the fourth try, they succeed. Message: Endure and persist, hold the vision, learn always. What was your struggle? What enabled you to persist? What did you learn?

5. Tell of the climactic moment when you "got it," when all the pieces fell into place, when you knew the right thing to do, and did it.

6. Bring your audience home with the results and the message or "lesson" of your story.

7. Give them the final word. Ask what stands out for them. Let the conversation unfold as it needs to; don't push an agenda; be open to whatever idea, insight, or personal sharing arises. This is the "melding" -- when one story catalyzes others, that then catalyze something new that no one thought of before.

(c) 2012 by Juliet Bruce. All rights reserved.

I'v always felt story telling to be a powerful tool for entrepreneurs and people in small business; and greatly enjoyed it.

ReplyDeleteThat's a great story. Reminds me of when I used to tell stories to my children at night. There was a structure - of course it had to involve them, it had to refer to something that happened during the day, there had to be some kind of dilemma, followed by solution and then a moral. Was a bit of a struggle some nights to meet the standard!

ReplyDeleteThank you, Rick and Outdoor Girl. OG -- you certainly did set a high standard for yourself! What a gift you gave your kids though -- a redemptive framework for dealing with life's challenges and hard realities.

ReplyDelete